"Let's not talk about the Economic

Partnership Agreements! We've said we rejected them -- for us, it's finished.

When we meet again, we'll discuss things, the EU will present their EPAs,

and we will present something else."- Senegalese President Maitre

Abdoulaye Wade (EU-Africa Summit Ends With Meager Results, Deutsche Welle

09.12.2007)

The deadlock between the African countries and the European Union (EU)

in the recent summit in Lisbon, Portugal scheduled to finalize the Economic

Partnership Agreement (EPA) probably has much wider implications than

just being a failure of the two continents to forge a partnership on economic

issues. The disagreement in the negotiations over trade facilitation issues

between the two blocs and the eventual rejection of the EPAs by the African

countries is not only a major setback for the EU, which had been trying

to impose its economic and trade agenda on the most backward continent,

but also marks a clear break in the historical relationship of the African

nations with their erstwhile colonial rulers.

The more significant aspect of this resistance to the EPAs by the African

nations is that it comes in the wake of an incumbent threat, well-emphasized

by the EU during the negotiations, of expiration of all provisions of

preferential treatment in European markets in case the Cotonou Agreement

were not replaced by EPAs by the end of 2007. The Cotonou Agreement signed

in 2000 between the EU and the African, Carribean and Pacific (ACP) states

ensured a continuation of the non-reciprocal, preferential market access,

granted to the ACP countries by the Lome Conventions. The EU in its campaign

for EPAs carefully underscored the point that the EPAs were an absolute

necessity for maintaining tariff-free zones in the EU markets for African

exports in future.

The EU is currently also the largest trading partner of Africa with a

trade volume of more than 215 billion euros in 2006. A number of African

countries are also dependent, some quite heavily, on the EU for aid and

development funds. The fact that these unfavourable contexts did not deter

the African nations from adopting a strong and uncompromising position

in the EPA negotiations definitely marks a departure from the traditional

donor-recipient relationship between the North and the South. This departure

was so evident that it could not be ignored even, in the face-saving joint

declaration that was signed at the end of the Lisbon summit that otherwise

ended in differences. The declaration carried the line- "We are resolved

to build a new strategic political partnership for the future, overcoming

the traditional donor-recipient relationship," (Ambitious EU-Africa

summit ends in trade deadlock, Guardian, Dec 9, 2007). The political leadership

of Africa clearly pressed for a 'partnership of equals' in the future.

Issues of disagreement in the EPA negotiations:

The haste with which the EU has pursued the EPA negotiations completely

showed that they preferred to remain oblivious about the issue that a

replacement of the Cotonou Agreement with the EPAs meant an important

change in the trade regimes for the African countries. While the earlier

Lome conventions and the Cotonou Agreement granted the ACP countries non-reciprocal,

preferential access to EU markets, the EPAs were in essence reciprocal

bilateral free trade agreements. From the very beginning, the different

economic blocs within Africa have been incredulous regarding the reciprocity

issue based on the apprehension that a sudden surge of European imports

in the African markets can adversely affect their already vulnerable food

production, food processing and infant manufacturing industries. On the

other hand, the nascent stage of development of African enterprises and

associated supply-side constraints did not promise much in terms of garnering

advantages from competitive access in the European markets.

In such a context, differences between the two blocs emerged on a whole

range of issues during the EPA talks. While the EPAs were projected to

be about the development of the African nations, a major debate surfaced

on the very definition of development in an earlier round of negotiations,

when the 16 country East and Southern African (ESA) grouping met the EU

in Brussels in November. The ESA countries defined development to be a

further strengthening of their agricultural and industrial production

base and demanded a list of development projects, with concrete financial

commitments, from the EU. The EU, in its effort to undermine such a notion

of 'development' and not concede any such commitments, suggested that

these demands be put outside the main text in a separate 'development

matrix'. The ESA as a counter strategy pressed for a legally binding clause

to be attached to the 'matrix', which the EU eventually also declined

terming the demands as a mere 'Christmas shopping list'.

The EU has also been unwilling to separately discuss agricultural trade

policy, which was the biggest concern for the African countries. The Common

Agricultural Policy (CAP) reform did not propose any elimination of domestic

support to European farmers but merely sought to shift the support measures

to categories in WTO that are considered to be non trade-distorting. The

African countries have been driven by the concern that their local agricultural

production and agri-based industries will be wiped out by competition

from subsidized European imports. They demanded that elimination of both

the domestic support and the export subsidies currently provided by the

EU nations be discussed as part of the CAP reform. This is an important

issue as a large part of the employment, especially for women, is generated

from these sectors in the majority of the African economies. The EU gave

a poor response to these concerns, maintaining that these were their internal

affair and cannot be bought under the scope of the EPAs.

There were major disagreements also over the scope of products that should

continue to receive protection and the time frame for tariff elimination.

The EU wanted the African economies to reduce protection to only 10 percent

of their products, which was completely unacceptable to the latter. The

EU also rejected the demand for a five-year moratorium on tariff dismantlement

that the African countries thought was necessary. This unbridled liberalization

of their economies was unambiguously rejected by the African nations.

The central argument for the sheer necessity of the EPAs that was forwarded

by the EU was to make the trade arrangement between the EU and ACP more

compatible with the multilateral trading principles. However, the EU has

vigorously tried to push WTO-plus positions on more than one occasion

during the EPA talks. The EU wanted agreements on some of the Singapore

issues, like investment, competition policy, government procurement, as

part of the EPAs. This meant that the African countries would have had

to concede vital ground that they had successfully gained in the WTO.

The aggressive mood of the EU was reflected in their asking for a liberalization

of public procurement by the African countries when the WTO negotiations

were at most dealing with transparency in government procurement. These

issues were dropped from the Doha Work programme essentially due to the

resilient opposition by the ACP countries along with other developing

nations in the WTO.

The EU went beyond its negotiating mandate by pursuing an agreement to

deregulate the entry of European investors and businesses in the ACP countries.

They were clearly asking for more than anything that they have achieved

in the multilateral negotiations. The EU also wanted a WTO-plus approach

with regard to liberalization of services even as the ACP countries clearly

stated that they are not in a position to make any commitment greater

than those made in the WTO. The uncompromising and aggressive attitude

of the EU made the African countries feel that they were being hurried

through a reform process that will have crucial implications for their

economies in future. The regional economic integration process that is

currently under progress in the African continent was also perceived to

be potentially hampered by the EPAs without any significant and compensating

economic gains.

This multiplicity of factors prompted the African nations to reject the

EPAs wholesale. The onus for the failure of the EPA talks primarily lie

with the EU as the Cotonou agreement had explicitly mandated that the

EPAs should be negotiated only with those ACP countries, which were in

a position to do so, and alternatives should be explored with other non-LDCs.

This was never recognized seriously by the EU in its approach to the EPA

negotiations.

Africa to Depend More on Asian FDI inflows?

The EU has been particularly wary of the recent increases in the Chinese

investment in the African continent. The Chinese economy, with its growing

demand for minerals and oil, has also engaged in larger volumes of trade

with several African nations. In 2006, the total trade that China had

with Africa amounted to 43 billion euros, the third largest by any single

country or block. A United Nations study on FDI in Africa in 2007 reveals

that the annual FDI inflows into Africa from expanding developing countries

in Asia like China or India have been lower than the FDI inflows from

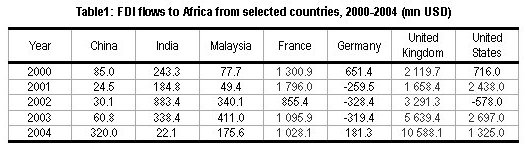

UK, USA or France at the beginning of the new century (Table 1).

|

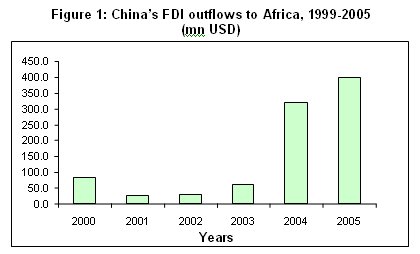

While the inflow of Chinese FDI in Africa has not been very large in the past decade, the European nations are alarmed by the recent surge in Chinese FDI inflows. According to the UN study, in the years 2004 and 2005, the volume of China's FDI in Africa has been USD 320 mn and USD 400 mn respectively (Figure 1).

|

Another concern for the EU is the large increase in the FDI stock of major Asian developing countries in Africa (Table 2). From Table 2, we can see that the FDI stock of China, India and Malaysia in Africa has significantly expanded in absolute terms over the last one and a half decades. In case of India and Malaysia, the African share in their total FDI stock has also substantially increased. Additionally, China cancelled debts amounting to USD 1.27 bn for 31 African countries in 2003 and has maintained a policy of giving debt relief and aid to African countries in the subsequent years. This has considerably increased the bargaining power of the latter in asking for similar debt relief from the IMF and World Bank.

|

Table 2: FDI stock of China, India and Malaysia in Africa and the World (mn USD) |

||||||

|

China |

India |

Malaysia |

||||

|

Regions |

1990 |

2005 |

1996 |

2004 |

1991 |

2004 |

|

Africa |

49.2 |

1595.3 |

296.6 |

1968.6 |

1.1 |

1880.1 |

|

Total |

1029 |

57200 |

3139 |

11039 |

3043 |

41508 |

|

Share of Africa |

4.78 |

22.79 |

9.45 |

17.83 |

0.04 |

4.53 |

The World Bank, while welcoming the growing Chinese investment in Africa,

skeptically observed that China should be more concerned about fighting

poverty, corruption and human rights abuses in Africa and not exacerbate

the existing problems of the continent. The response of the African leaders

to the FDI and aid inflows from China has been quite different, declaring

Africa to be mature enough to deal with newer developing countries. In

the words of Senegalese President Wade-“Africa defends its interests,

its economic interests. China and India have become major partners for

Africa” (Africa says big enough to cope with China courtship, Reuters

Africa, Dec 9, 2007). In the rejection of the EPAs, the African economies

have conveyed a clear message to the North that they prefer to depend

increasingly on a South-South cooperation strategy in the coming times.

Implications of the New Development:

The outright refusal to sign the EPAs by the African nations is undoubtedly

a watershed event in the history of bilateral trade agreements. It has

more than one implication for the developing world. First, there has been

a growing awareness among the African people regarding the negative impacts

of the reforms process that their countries have been adopting for some

time now. There were widespread campaigns by civil society organizations

which resulted in 'A Global Call for Action to Stop EPAs' in 2006. This

call was jointly issued by thirty CSOs, including global actors like the

Action Aid, Oxfam International and Christian Aid, when they got organized

on a single platform-the African Trade Network (ATN) in Harare. The earlier

UN Secretary General Kofi Annan had also pointed out to the African head

of states that-'…The prospect of falling government revenue, combined

with falling commodity prices and huge external indebtedness, imposes

a heavy burden on your countries and threatens to further hinder your

ability to achieve the Millennium Development Goals' (Six Reasons to Oppose

EPAs in their Current Form, www.twnafrica.org).

The democratic, affirmative action meant that it created a significant

pressure on the respective African governments to protect the interest

of their people. It is clearly a changed situation from the times when

the EU and other developed nations could manipulate authoritarian regimes

to unilaterally impose their trade and economic agenda on the African

people. The rejection of the EPAs by Africa will potentially inspire other

LDCs to protect their own interests more vigorously in bilateral agreements

with the developed nations.

The other important implication of this development has been the stronger

resolve of the African political leadership to strive for greater South-South

cooperation. The rise in the economic power of Asian developing countries

like China and India has provided more leverage to African economies in

their negotiations at the bilateral and multilateral levels. The message

from the African nations has been one that they are more inclined to enter

into cooperation with other developing nations than sign trade agreements

with the North, which compromise their own interests and endanger the

livelihoods of their people. The outcome of the Lisbon summit clearly

points out that the EU and other developed nations will have to overcome

their colonial mindsets if they want to reach economic agreements with

African nations in the emerging world economic scenario.