On

21 January 2003, the Indonesian government, under

pressure from its legislators, declared that it wanted

to break free of its commitments to the IMF. Chief

Economics Minister Dorodjatun Kuntjoro-Jakti told

an annual meeting of donors that the government did

not wish to extend the existing $4.8 billion loan

package with the Fund. This credit line under the

Extended Fund Facility (EFF), of which up to $3 billion

has already been disbursed, is scheduled to expire

at the end of this year. The announcement came one

day after the government rolled back its most recent

price increases on utilities--a key plank of the economic

reforms agreed to with the IMF--after a two-week long,

nationwide protest.

On 1 January, the government of President Megawati

Soekarnoputri had raised the prices of fuel (22 per

cent), telephones (15 per cent) and electricity (6

per cent). These price increases were directly in

line with the government's commitment under the IMF

programme to cut state subsidies and narrow the budget

deficit. After the prices of utilities were raised,

protesters hit the streets almost daily against the

eighteen-month-old government. The subsidy cuts combined

with inflationary pressures have hurt impoverished

Indonesians the most. Inflation touched 10 per cent

last year and the government forecasts a 9 per cent

rate this year. In a country where more than half

the population of 220 million live on less than $2

a day, and more than 40 million people are unemployed,

these subsidy cuts really hurt the majority of the

people.

The protests continued despite a government proposal

to indefinitely delay the increase in telephone charges.

Clearly, in a situation, where only 3 per cent of

Indonesians have fixed telephone lines, delaying the

rise in phone charges would have no impact and the

demonstrators rejected the proposal saying it would

be of no help to the poor. It was the fuel and electricity

price hikes that were more severe and the target of

popular anger. The World Bank--whose backing was vital

for Indonesia to gain nearly $3 billion in financial

aid at a donors' meeting to be held the following

week--threw its weight behind the government, saying

that the price hikes were necessary to wean the country

away from hefty subsidies. Although the popular protests

were not expected to escalate into deadly riots like

those that had toppled former President Soeharto in

1998, the Megawati government, which faces elections

next year, decided not to take any further chances

and reduced the price hikes. The proposed new prices

raise the cost of fuel by only 6.5 per cent, instead

of the 22 per cent increase put in place in January.

This backing down on fuel subsidies, further propelled

the government towards making a decision on its IMF

loans.

The decision to part ways with the IMF, in fact, comes

as the culmination of years of discontent brewing

within Indonesia, ever since the East Asian financial

crisis savaged the country. There have, for long,

been many in the various Indonesian governments who

resented what they saw as interference by the IMF

and the World Bank in policy-making, and there have

been several battles of will between the IMF and the

Indonesian government over the implementation of anti-poor

'structural adjustment' measures, amidst increasing

protests by the people. This had led to the country's

highest legislative body, the People's Consultative

Assembly (MPR), urging the government in October 2002

to stop its cooperation with the IMF. In fact, it

issued a decree requiring the government not to extend

the current IMF programme when it expires late this

year, as it believed that the Fund could not be of

much assistance to overcome the country's economic

crisis. Despite having been 'nursed' by the IMF for

five years, the Indonesian economy was only getting

worse because the 'recipes' provided by the Fund had

proved ineffective. It was suggested that it would

be better for Indonesia to overcome the economic crisis

on its own by making optimum use of its capacities.

It was in October 1997 that Indonesia's recent tryst

with the conditionalities-attached IMF loan package

began, when the government turned to the Fund for

an emergency debt package totalling $43 billion. This

was soon after Indonesia's currency began sliding

following the dramatic reversal of capital flows into

the country, itself triggered by the 'contagion effect'

that followed the devaluation of the Thai baht in

July 1997.

Under its first three-year US$5 billion Extended Fund

Facility to Indonesia, the IMF prescribed its now

much-maligned tight macroeconomic formula: i.e. a

strict monetary policy to stabilize the exchange rate

and a tight fiscal stance to reduce the fiscal deficit.

Interest rates were immediately increased in order

to stabilize the rupiah. However, despite the IMF's

intervention, the high interest rates failed to influence

the exchange rate to any significant degree, as capital

outflows continued. Further, the high interest rates

led to a severe liquidity crunch. As the economy went

into contraction, there was a steep rise in company

closures and unemployment. While the Soeharto government

maintained that the rapid spread of poverty made increased

subsidies on items such as food and fuel essential,

the financial markets construed President Soeharto's

failure to embrace fiscal austerity in the January

1998 budget as a reflection of the IMF's inability

to enforce discipline on the government. This led

to further collapse of the rupiah, driving about 75

per cent of Indonesian businesses to technical bankruptcy

due to the large foreign debts they had accumulated

over the period of financial liberalization prior

to the crisis. In this increasingly desperate situation,

true to its tradition, in a new Letter of Intent (LI)

issued in January 1998, the IMF secured a greater

number of even more stringent reform commitments than

in the October LOI. However, the introduction of this

second package of IMF reforms also did not lead to

immediate stabilization.

The January agreement led to sweeping reforms including

the dismantling of state and state-enforced monopolies,

elimination of consumer price subsidies, phasing out

of utility subsidies, and further trade and investment

liberalization. The specific steps to liberalize trade

and investment included reducing tariffs on all imported

foodstuffs products to 5 per cent and cutting non-agricultural

tariffs to 10 per cent by 2003; opening banks to foreign

ownership by June 1998; and lifting restrictions on

foreign banks by February 1998. Since the start of

the loan programme, the IMF has also persistently

pushed the Indonesian government to further open its

economy through various measures like the elimination

of monopolies and cartels, reform of the wood sector,

privatization of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and

downsizing of the National Logistics Agency (BULOG).

As the International NGO Forum on Indonesian Development

(INFID)[i] has argued, the IMF has been constantly

demanding rapid reforms, including quick sales of

the Indonesian Banking Restructuring Agency's (IBRA)

assets and privatization of hundreds of state-owned

companies, regardless of the capacity of the state

to carry out the reforms in the time-periods envisioned

and the long-term impact of these programmes on the

Indonesian economy or the poor. Each time there was

a perceived delay in implementing any of the 'crucial'

measures which the country had committed itself to

in the Letters of Intent with the IMF, the Fund delayed

its country review, on which the next tranche of IMF

funds as well bilateral loans (i.e. from lenders in

the CGI belonging to the Paris and London Clubs) hinged.

These IMF interventions have resulted in the Indonesian

economy being the worst affected among the five East

Asian crisis-hit economies.

Prior to the 1997–98 financial crisis, Indonesia

had a relatively comfortable debt situation. The government

borrowed primarily from the World Bank, Asian Development

Bank, and a group of bilateral donors grouped in the

Consultative Group on Indonesia (CGI), for funding

its development budget. Establishing this as a convention,

the government avoided domestic borrowing, and Indonesia's

debt/GDP ratio was considered sustainable by the multilateral

bodies and other donors. Following the oil price crash

in the early eighties, Indonesia undertook banking

and financial sector liberalization without adequate

or prudential protection of its system. While its

debt management policies were considered adequate,

its financial liberalization which exposed the Indonesian

economy to the 1997 currency crisis was, until then,

considered a successful experience.

The situation changed in 1998–99, when Indonesia

for the first time contracted a large volume of domestic

debt to finance the bailing-out costs of the country's

crisis-hit banking sector. The bail-out was necessitated

by the crisis that occurred despite a decade of ostensibly

successful World Bank/IMF-promoted financial liberalization,

and because of the fact that the Indonesian government

had followed IMF advice to immediately restructure

its crisis-hit financial sector. With at least 70

per cent of bank loans estimated to be non-performing

following currency devaluation and the financial crisis,

at the direction of the IMF, the government closed

sixteen insolvent banks in November 1997, without

adequate preparation. The result was a near-collapse

of the entire financial system, which in turn forced

the government to recapitalize the banking system

by issuing bonds to domestic commercial banks and

the central bank. This created an estimated US$80

billion in new domestic debt, even as successive governments

after Soeharto inherited the substantial foreign debts

accumulated during his time. As a consequence, Indonesia's

official debt burden increased from 27 per cent of

GDP prior to the crisis to more than 100 per cent

by the end of 1999, before declining gradually. In

fact, Indonesia, which was ranked as middle-income

and middle-indebted before the crisis (at the same

level as its neighbours Thailand and the Philippines),

now belongs to the SILIC (severely indebted low income

countries) category, whereas none of the other crisis-hit

East Asian countries such as Malaysia, Thailand or

Korea are in the SILIC group.

The IMF has refused to assume responsibility for the

way its wrong policy advice exacerbated the crisis

and stalled the subsequent recovery. Further, instead

of providing a long-lasting solution to the debt burden

which they themselves had helped create and accumulate,

the multilateral bodies and bilateral donors have

continued to insist on policy measures requiring stringent

constraints on expenditure and increased revenue mobilization,

for servicing this sharply increased debt burden.

This has crippled the capacity of the Indonesian government

to mitigate the impact of the crisis on vulnerable

groups. From an estimated 9.6 per cent in 1996--the

year before the Asian financial crisis--Indonesia's

poverty rate doubled to 19 per cent in 2001. The government

has sought to support the increased number of people

who have fallen below the poverty line with three

kinds of measures: (1) temporary income transfers,

through rice distribution to the poor at subsidized

prices; (2) income support, through employment creation

and by support for SMEs and cooperatives; and (3)

preserving access to critical social services, particularly

education and health.[ii] However, most of the government's

efforts to mitigate the impact on the poor have been

limited by severe budget constraints. According to

Bank Indonesia data, in 2001, total amortization and

interest payments on Indonesia's domestic and foreign

debt reached almost 35 per cent of central government

expenditure. INFID (2001) estimated that the total

amount of the government's debt service would have

increased further to around 38.7 per cent of total

spending in 2002. In comparison, critically needed

development spending declined from about 45 per cent

of total government expenditure in 1993 to 33 per

cent in 2001, with more than half of this sum stemming

from donor-financed development projects. According

to INFID (2001 and 2003), social spending also suffered

a dramatic decline, around 40 per cent in real terms

below the spending in 1995/1996.[iii]

Meanwhile, notwithstanding the economic fall-out of

the October 2002 Bali terrorist attack, the 2002 budget

deficit is estimated to have fallen to under 2 per

cent of GDP, down from 3.6 per cent in 2001.

The windfall export earnings due to the oil price

rise contributed to this. The year 2002 also witnessed

a large reduction in Indonesia's public debt burden.

The public debt to GDP ratio fell from about 90 per

cent at the end of 2001 to almost 70 per

cent by the end of 2002. Apart from the continuous

reductions in government spending, this was achieved

through major government disinvestment programmes

and privatization. After the recapitalization of private

banks, the IMF exerted strong pressure on the government

to divest the assets it held in the form of banks'

shares. The Indonesian Bank Restructuring Agency (IBRA)

has now disposed of over half of the original portfolio

of NPLs taken over from weak and closed banks. In

2002, the government also sold its majority stakes

in two banks and in the international telecommunications

company--Indosat. In fact, the government exceeded

its 2002 privatization target of Rp 6.5 trillion,

collecting Rp 7.7 trillion. However, according

to INFID (2003), this divestment has produced relatively

small revenues compared to the high costs of servicing

the government bonds that had been issued to recapitalize

those banks. Further, the privatization programme--particularly

the sale of state-owned enterprises and assets while

simultaneously retaining the debt--has aggravated

the domestic debt burden.

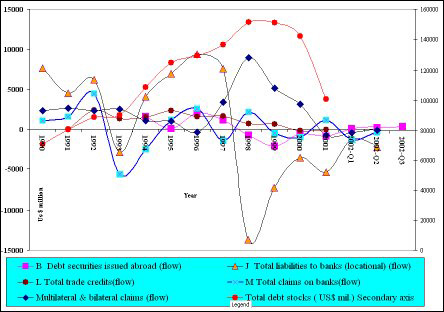

The external debt stock has also fallen from its peak

at the end of 1999. As Figure 1 reveals, annual debt

payments until almost 2000 were achieved through swapping

of funds across the available channels for raising

funds. But, since 2000, the trends in all liabilities

(total liabilities to banks, trade credit, claims

on banks, multilateral and bilateral claims) have

turned negative, reflecting the mounting debt repayment

and servicing obligations for the country. It is thus

evident that the economy will continue to face a severe

liquidity crunch as outflows continue. Even though

Indonesia had sought rescheduling from the Paris Club

in 1998, 2000 and 2002, these agreements are only

for bilateral debts and exclude debts to private bond-holders

as well as multilateral creditors. Also, the rescheduling

excludes the best terms (including partial write-offs)

available under the Paris Club conditions. Further,

the enforcement of the Paris Club agreement is conditional

upon the progress of the programme laid out in the

government's Letter of Intent to the IMF.

Figure 1: Indonesia's External Debt: Flow Analysis,

1990-2002 Q3

|

|

| Source: Based on Joint BIS-IMF-OECD-WB External Debt Statistics available at http://www1.oecd.org/dac/debt/. |

Despite its low income and SILIC status, the IMF and the World Bank consider that Indonesia does not qualify for debt relief under HIPC. The IMF and World Bank's assessment that Indonesia's debt is sustainable is sustainable is compromised by misleading and over-optimistic assumptions about Indonesia's growth rate, as well as by their status as creditors. According to the latest estimates from the Central Statistics Agency, growth rates in GDP, investment and export fell in 2002. According to Bank Indonesia data available till March 2002, net private capital inflows that turned negative in end-1997 have remained negative ever since. Another report has stated that while all the ASEAN countries have registered positive growth in FDI, Indonesian FDI inflows have failed to recover. An American-led attack on Iraq could further hurt investment in Indonesia, which has the world's largest Muslim population. A war in the Middle East is expected to send shipment costs soaring by more than a third and further erode cost-competitiveness. With a significant drop in tourism expected due to concerns about internal security following the Bali attack, and considering the effects of a slowing global economy since the previous forecast, growth in 2003 is expected to be about 1 percentage point weaker than previously estimated, or down to 3.5–4 per cent. On the other hand, while the share of oil and gas exports in total Indonesian exports showed a decline, from 31 per cent in 1992 to about 22 per cent in 2001, the share of oil and gas imports in total imports rose, from some 10 per cent in 1992 to 18 per cent in March 2002. Under these circumstances, servicing just the existing foreign and domestic debts will remain a huge burden on the country's development expenditures in the perceivable future, even without taking on new debt.

Those responsible for the creation of Indonesia's unpayable debts--the G7 creditors, the IMF and the World Bank--do not bear the financial risks associated with the loans they made to Soeharto, even as they continue to blame cronyism and corruption and seek legal and corporate reforms. In spite of the fact that a large chunk of this public debt in effect arose from their own misguided advice to the Indonesian government, the IMF and the CGI persist with their insistence on continued reduction of Indonesia's large public debt. It is clear that most of the costs arising from the failure of IMF/WB-supported liberalization of Indonesia's financial market and the malfunctioning of the banking system have been transferred from private financial institutions-- whether domestic or foreign--to the Indonesian public. This apportioning of costs between the public and private sectors has highly inequalizing consequences. At one level, the combination of a credit squeeze (the fact that the mandatory capital adequacy ratio was increased to 8 per cent last year as part of the government's programme to strengthen the banking system, also contributed to the credit squeeze), falling government expenditure for development purposes, and the increasing role of the private sector in public utilities with collusive pricing behaviour has led to unacceptable falls in the disposable incomes of Indonesian consumers. However, the inflexibility of the IMF in its fiscal deficit targets has made it difficult for the government to maintain subsidies at levels commensurate with falling income levels. At another level, the global economic slowdown, the uncertainties associated with the current conjuncture and the lack of international liquidity means that there are very poor prospects for quick resumption of export growth or of private capital flows into the country. Thus, by deciding not to extend the IMF loan, the Indonesian government has climbed out of the tough fiscal austerity prescriptions that have been hurting millions of its poor.

After initial uncertainty, Jakarta's donors under

the Consultative Group on Indonesia (CGI) have signalled

that they will give the nation the $2.6 billion aid

it wanted for 2003, despite its backing down on fuel

price. Clearly, the reality is that Indonesia is too

big and too important to fail, as the Economist has

conceded candidly. The IMF and the World Bank--key

proponents of raising prices on utilities to cut costly

subsidies--have now agreed that Jakarta's backdown

has to be viewed against the fact that social unrest

is not desirable and risks derailing what has been

accomplished thus far. The World Bank, which is leading

the Group's negotiations, had warned Indonesia earlier

that resuming subsidies might jeopardize requests

for new loans. Apart from being a big country, the

fact that Indonesia has been afflicted with political

instability and Islamic fundamentalism has also influenced

the external decision-making process, especially in

the face of the 2004 elections. Indonesia, though

an ally of the US in the global war on terrorism,

opposes military action in Iraq. In the current conjuncture,

the donors are acutely aware of the danger of social

unrest in the world's most populous Muslim nation,

which has been buffeted by five years of economic

turmoil since the 1997–98 Asian economic crisis.

This is why, while earlier pleas that the Indonesian

government is unable to repay its debt without imposing

unbearable hardship on the poorest sections of society

fell on deaf ears and the government was forced to

undertake drastic measures, the present turnaround

by the Indonesian government is seen as justifiable.

Recently, social and political unrest in many debt-ridden

countries, primarily caused by conditionalities-imposed

economic hardships, has come to be seen by the World

Bank and the IMF as derailing the 'hard-won' financial

stability in those countries; they have therefore

allowed some flexibility in the reform measures demanded

of these countries. Clearly, however, the more the

desirable thing would be to avoid, in the first place,

the ideological prescriptions that lead to such mass

suffering. At another level, should not the multilateral

bodies, which are linking up their aid and loan packages

to democracy-linked electoral reforms in debtor countries,

be viewing the popular protests as indicators of increasing

political participation by the affected populations

in these countries? Apart from democratic reforms,

it is indeed interesting to see that the Bank and

Fund-advocated decentralization, which on the whole

is acknowledged to have proceeded satisfactorily,

is now being perceived by them as a problem for both

existing businesses and prospective investors, in

terms of new and conflicting regulations and taxes

at the regional level.

It has been seen time and again in East Asia, Latin

America (where Argentina has witnessed the most recent

devastation) and elsewhere that IMF–World Bank

programmes which are driven by an absolutist ideology

do not work at all in crisis scenarios, and in fact

make them worse. It has also been seen that there

is very little scope for these leviathans to change

their course when confronted with the crises, failures

and suffering perpetrated by their misguided policies

until the consequences seem to affect the interests

which they themselves represent. In a recent instance

of reversal of stance, four years after describing

Malaysia's decision to peg its currency to the dollar

during the financial crisis in 1998 as a 'retrograde

step’, the IMF has said that the peg is an 'anchor'

of a rebounding economy.[iv] In a December 2002 report,

the Fund has stated that Malaysia is better off for

having ignored its advice. Clearly, however, other

East Asian crisis countries that followed the Fund

advice are not going to benefit at all from this admission

of the IMF. Further, despite such pronouncements at

convenient times, the Fund continues to impose the

same set of macroeconomic measures on countries facing

a payments crisis. For instance, under an interim

agreement reached after a year of negotiations, the

Fund agreed to roll over, or reschedule, about $6.8

billion in Argentinian debt that is due through August.

But it is feared that even the modest terms imposed

as part of this agreement will include imposing sharply

higher utility rates, creating bigger budget surpluses

and severely restricting the amount of money in circulation,

all of which will further deteriorate the prospects

for economic recovery in that country. Thus, apart

from delinking itself from its financial responsibilities

in taking on the risks of its sovereign credits, and

perversely gaining from major policy errors and going

on to compound them, the Fund has demonstrated that

it has no moral responsibility either.

Against this backdrop, Indonesia's decision to finally

ask the IMF to pack its bags rather than continue

to follow the path to utter deprivation for its citizens,

clearly seems to be the most 'rational' choice that

could have been made. This is the latest in a series

of instances where a number of countries, including

Botswana, have either opted out of IMF programmes

or refused to initiate the structural adjustment programme

(SAP). This is clearly reassuring and holds the promise

of encouraging further such 'rational' choices among

countries facing the pressures of neo-liberal reform.

This will also encourage countries to turn towards

seriously addressing their domestic socio-economic

problems.

In the final analysis, it is important to ensure that

small developing and least developed countries do

not get left out in the geo-political power game.

While individual initiatives by large developing country

borrowers have immense significance of their own,

across the South, the struggle for forcing broader

and deeper changes in the parameters within which

the multilateral bodies operate, must continue.