China's

rate of economic growth during the last quarter of a century has left

many countries craving for a similar experience for their economies, and

these countries have been trying to replicate the Chinese 'success' story.

While there is much debate about the actual rate of growth China has witnessed

ever since it went in for state-controlled and selective opening up of

certain sectors of its economy, economists are unanimous in their opinion

that the growth has not been insignificant in the sectors and regions

that were opened to foreign participation. However, what is worrisome

is the fact that this growth has been an extremely skewed one. There is

growing imbalance between sectors, and both between and within regions.

According to a study by Dali L. Yang and Houkai Wei[1],

the average annual growth rates of GNP and industrial gross output value

(GOV) in the inland regions of China have been always lower than those

achieved in coastal China. Further, the study states that the difference

between these growth rates have gradually increased since 1980. Gaps are

also arising between the urban and rural populations in China.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1992 can be considered as the year in

which China decided to speed up its process of economic reforms. Since

then the regional gap has increased further. In 1998, the per capita GDP

of Shanghai, the richest provincial unit, was twelve times that of Guizhou,

the poorest province. In the year 2000 the gap between incomes in coastal

and inland regions went up to 57.3 per cent.

Similarly, urban incomes are growing faster than rural incomes. The per

capita disposable income of the urban Chinese rose from 5425 Yuan in 1998

to 7703 Yuan in 2002, a rise of almost 42 per cent in five years. Over

the same period, rural disposable income per capita rose a meagre 14.5

per cent, from 2162 Yuan to 2476 Yuan. However, both these increases were

in nominal terms. If one considers price increases in real terms over

this period, per capita urban disposable income rose 13.4 per cent between

1998 and 2002, while rural per capita disposable income rose a mere 4.8

per cent[2]. A survey conducted by the Institute

of Economics of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, using data from

1988 and 1995, reveals that rural individuals make up most of those in

the lower decile income groups, while in the higher decile groups, urban

residents predominate. An important factor behind the faster growth of

urban incomes in China in the post-reform period is income from property,

which was made possible through commercialization and privatization of

the erstwhile public housing system. While the property income of the

urban Chinese accounted for a mere 0.49 per cent of total individual income

in 1988, by 1995 the share had gone up to 1.3 per cent.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

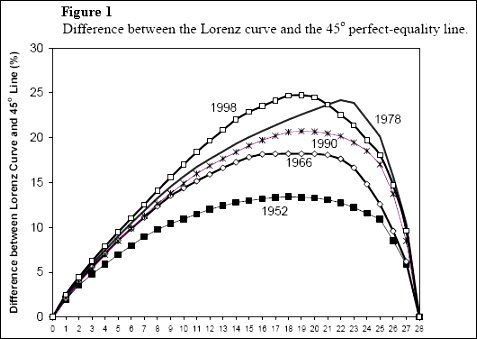

The gap between rural and urban incomes

narrowed from 1978 all through the 1980s owing to the start of the rural

reform period which saw the introduction of the household responsibility

system and the simultaneous withering of the commune system. However,

as we will observe later, the dismantling of communes increased inequality

within rural China, even the urban–rural divide started rising again

in the 1990s. This is evident from the Lorenz curve given below:

|

|

|

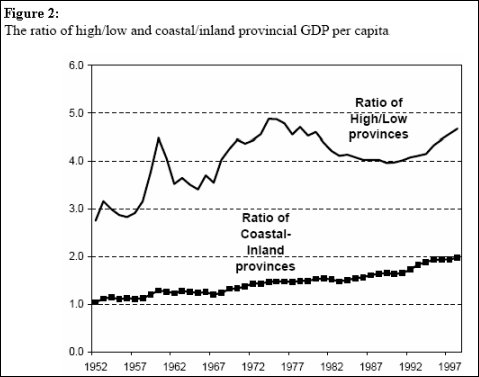

Figure 2 gives the ratio of per capita

GDP of provinces with the highest GDP to provinces having the lowest GDP

per capita[3],and also the ratio of per capita

GDP of coastal provinces to that of inland provinces. Both ratios witness

more or less steady increases over the period under study, with the latter

exhibiting a more secular rise. The ratio of per capita GDP of high-income

and low-income provinces also exhibits a rising trend, but the ratio had

fallen in intermittent years, particularly during the first half of the

1960s and between 1975 and 1990. The differentials of per capita income

in rural and urban areas between 1978 and 1995 show an almost similar

trend, but according to figures available in an article by Zhao Renwei[4],the

urban–rural divide started rising again from the middle of the 1980s.

|

|

|

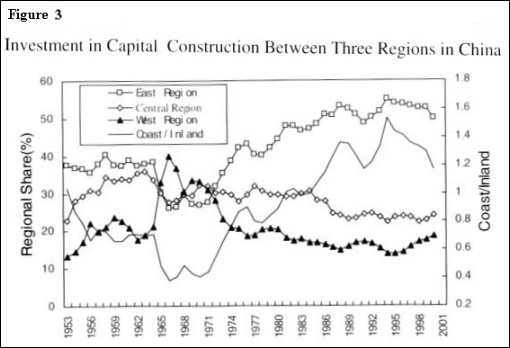

The main reason behind the increasing

disparities between coastal and inland China, as well as between rural

and urban China, is the coastal development policy pursued by the Chinese

government. This has led to capital, both foreign and domestic, being

invested mostly in the coastal regions of China, with the inland areas

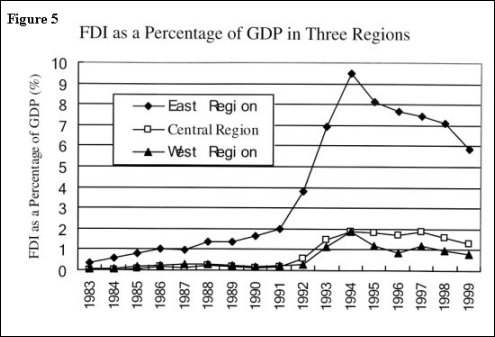

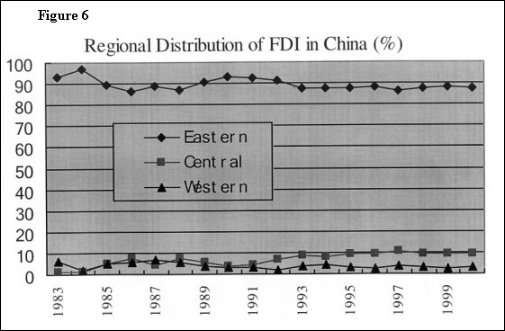

being starved of funds. As Figures 3-6[5]

below reveal, almost all the investment that has come to China, particularly

since the country went in for state-controlled liberalization, has gone

to the eastern region. In 2001, 50 per cent of all FDI went to just three

locations—Guangdong province, next to Hong Kong, the city of Shanghai,

and its neighbour, Jiangsu province. Most of the rest of the money went

to other locations up and down the coast. Inland, and indeed in some places

along the coast, the flow was just a trickle. In 2001, Guizhou, China's

poorest province and home to nearly 40 million people, attracted less

than $30million[6].

|

|

|

|

As a consequence, even the growth of peripheral

and satellite industries and services that usually develop in the neighbouring

areas of any industrial town or city, have been limited to the rural areas

in the coastal region of the country. This is brought out by Table 3,

which gives region-wise data for the value of exports achieved by rural

enterprises in China. Within a span of eight years, the share of the eastern

region went up from 82.8 per cent to 92.6 per cent, while that of the

central and western regions fell from 14.6 per cent to 6.5 per cent and

2.6 per cent to a meagre 0.9 per cent, respectively.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The majority of those among the Chinese

people who belong to the minorities and the rural poor reside in the inland

regions. An excessively wide regional gap could not only undermine social

stability but also disrupt political stability and spur secessionist activities.

In a bid to address the issue of growing inequalities in the country,

the Chinese government seems to have taken steps to bridge the spiralling

gap between the coastal and inland regions of China, as well as that between

urban and rural areas. The government's assessment was that the widening

gap was a result of the decline in the performance of rural enterprises

in coastal and inland China, and at the 5th Conference of the 7th National

People's Congress held in March 1992, it decided to 'support vigorously'

the development of rural enterprises in the central and western regions

of China. In that year the People's Bank of China offered an additional

2 billion Yuan worth of bank loan ration and 3 billion Yuan worth of rural

credit cooperative loan ration on the basis of original credit planning,

with a view to supporting rural enterprises in central and western China.

This additional amount was to be provided annually for a period of eight

years, from 1993 to 2000. Another annual special loan worth 5 billion

Yuan for the years 1994–2000 was pledged by the State Council in

September 1993, to support rural enterprises in these regions. The Agricultural

Bank of China also set up a 100 million Yuan special discount loan facility

from the last quarter of 1992 to cater to rural enterprises in minority-nationality

regions in the country. These regions included Guangxi, Ningxia, Xinjiang

and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, and the provinces of Yunnan, Guizhou

and Qinghai. Besides, the Chinese government also announced certain tax

exemptions (which included a three-year exemption from income tax for

all newly established rural enterprises in certain areas) for rural enterprises

in central and western China.

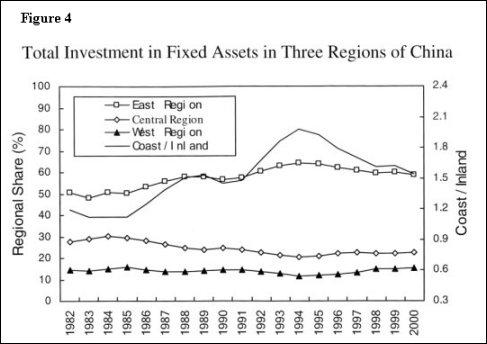

That the efforts of the Chinese government to boost investment in the

backward regions has yielded results can be observed from Figures 3 and

4, which reveal that the coast to inland ratios of investment in capital

construction and total investment in fixed assets have come down in recent

years. Also, local governments of the coastal region have, of late, been

encouraging and laying stress on supporting rural enterprises of underdeveloped

regions, as rural enterprises in the coastal region are suffering from

diseconomies caused by overconcentration and the existence of an inter-regional

dual structure. The development of rural enterprises in inland China is

further expected to curb the constant migration, both legal and illegal,

of labourers from these regions to coastal China in search of a livelihood,

thereby easing the pressure on the infrastructure of the coastal region.

However, despite the proclaimed efforts of the Chinese government to spur

economic activities, growth and development in inland China, things did

not turn out as expected for the central and western regions. Rather than

helping the inland regions, the government's policies seem to have helped

the developed coastal regions through the supply of cheap labour and raw

material from inland China. The policy initiated by the Ministry of Agriculture's

Department of Rural Enterprises in China, avowedly to promote mutual economic

benefit and common prosperity, in essence has meant that while coastal

China will witness the development of high and new technology-based industries

and the growth of an export-led economy, the emphasis in inland China

will rest on a strategy of resource exploitation. Faced with a rapid rise

in wages in coastal China (the wages in eastern China being about 1.5

times higher than in inland regions), the developed coastal areas of China

will constantly try to transfer only low-grade labour-intensive production

processes to central and western China while trying to replace labour

with capital in the medium to long run.

Heavy exploitation of the mineral resources of inland China alongside

a booming raw and processed material industry will soon lead to environmental

degradation and resource depletion of the region, resulting in long-term

calamity. Further, as one must be aware, the terms of trade have historically

moved against primary commodities, and there is no reason to believe that

for exports of inland China, the trend would be defied.

Projects like the Three Gorges Dam and river interlinking, despite being

criticized for disrupting the ecological balance, flooding some of the

most fertile lands in the country and causing environmental degradation,

are expected to reduce inequalities. In the initial stages such projects

are expected to create employment in huge numbers, thereby increasing

the income and purchasing power of the people in the provinces in which

they are implemented. However, it is in these same regions that such projects

displace large sections of the population. Not only do many of them fail

to be adequately resettled, even those who are resettled find it difficult

to earn a livelihood. Being resettled in a place where the skills of the

migrants might not even be in demand, these people, particularly the older

ones among them, may find themselves without any purchasing capacity.

Resettlement policies in China have so far benefited the rich among those

displaced more than they have helped the poor. With rural property costing

less than urban homes, migrants who have been displaced from rural areas

get much less compensation in comparison to those displaced from urban

homes. As a result, rural migrants are often forced to borrow money from

relatives and friends to build new houses—and so start their new

lives with a mountain of debt. Rural migrants are also more likely to

be forced to move farther away than urban migrants, as well as face daunting

economic and social challenges in adapting to an unfamiliar environment[7].

While the experts who were a part of the official feasibility study team

for the Three Gorges Dam have claimed that those who were displaced because

of this project will all be resettled in the reservoir area, and that

40 per cent of the rural migrants could be redeployed in non-farming jobs,

researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences have said that the lives

of these migrants will not necessarily be better or even the same even

if the 'local resettlement' target is met. The researchers tracked a small

number of rural migrants in the Wuqiao district of Wanxian city, and found

that most of them were significantly less well off than they had previously

been. Both newcomers and existing residents had only half as much land

as they did before resettlement. The amount of farmland available per

person also had declined dramatically after the influx of migrants, and

the resettlement site failed to provide new work for individuals squeezed

off the land. Almost all the households monitored in the study had suffered

increased unemployment and a sharp decline in income. Since most of the

land available for relocation under the Three Gorges project was barren

and unsuitable for cultivation, many of those displaced were reluctant

to move to such inhospitable conditions.

Even though the official experts had pledged that everybody displaced

by the Three Gorges project would be rehabilitated within the reservoir

area, the actual has relocation belied their promises. Soil erosion has

become a serious problem in the Three Gorges area with the expansion of

farmland and construction of hundreds of new settlements. To relieve the

pressure on a fragile ecosystem, in 1999, Premier Zhu Rongji announced

a policy shift in favour of moving migrants to distant parts of the country.

This decision to move 125,000 migrants far from their homes was not part

of the original resettlement plan. Many of the migrants found it difficult

to cope in their new, unfamiliar physical and social environments, and

with conflicts with 'host communities'. Migrants to distant areas found

that they could not speak the local dialects and faced tremendous problems

in communicating. In March 2002, thousands of rural migrants who had been

moved under Zhu Rongji's policy to Badong county in Hubei province, complained

about substandard resettlement conditions and asked to be relocated. To

maintain social stability, they were moved again. However, such additional

relocation has only led to a further rise in the costs of the project.

Most of the soft loans that the Chinese government and banks had pledged

for rural enterprises in inland China in the early 1990s have not been

forthcoming. With the banking system in China also undergoing reforms,

more emphasis is being placed on the profitability of the projects and

not on issues like employment generation and reduction of inequality.

The People's Bank of China had initially pledged an annual loan of 5 billion

Yuan at low rates of interest to support rural enterprises in central

and western China, but later the bank decided that it would provide the

loan purely on a commercial basis. Even then a major part of the promised

funds were not made available, and loans provided by the agricultural

banks for rural enterprises in inland China were on the decline. Agricultural

banks and credit cooperatives still account for almost three-fourths of

the rural enterprise loans in the eastern region of China.

Finally, even the tax benefits initially on offer for those setting up

new enterprises in rural areas in the central and western regions of the

country were mostly withdrawn under the new tax policies that are being

implemented in China. About four-fifths of the taxes paid by rural enterprises

go to the central government, and as such, local governments cannot support

the development of rural enterprises in those regions through preferential

tax policies. Although the new tax regime has exempted all items of export

from value-added tax and consumer tax, the western and the central regions

hardly benefit from such largesse as less than 10 per cent of the exports

of rural enterprises come from enterprises located in these regions.

The Chinese government has recently woken up to the necessity of addressing

the concerns of the nation's backward provinces. The Tenth Five-Year Plan

(2001–2005) in China has the narrowing of regional inequalities

as one of its principal objectives. It pushes for sustainable development—with

increased productivity in agriculture and in industrial state-owned enterprises

(SOEs). The Plan also intends to create jobs by promoting labour-intensive

activities, including services, and developing collective, private and

individual businesses. The Plan hopes to create 40 million new urban jobs,

and to safeguard the natural resource base. Rural reforms, as outlined

in the Plan, aim at accelerating agricultural diversification and raising

incomes. The new National Poverty Reduction Plan for 2001-2010 adopts

a more comprehensive approach with better targeting of the deprived population

in the backward provinces of western China. The Tenth Plan also calls

for 'coordinating economic and social development'—by paying greater

attention to quality-of-life issues, including investing in human capital

(e.g., anti-poverty measures, better education), protecting natural capital

(e.g., by enhanced ecological conservation and environmental protection),

and improving social protection (e.g., by strengthening the social security

system). In particular, China's Tenth Plan outlines the need for developing

the country's economically and socially lagging western and central provinces—by

fostering economic development zones through investments in strategic

physical infrastructure for transport, water resources management, energy

and mining, accelerating other development objectives as cited above,

and introducing advanced technologies to upgrade local industries and

increase competitiveness.

It is essential that the competitiveness of China's backward regions improves,

not only in primary commodities and as providers of raw materials for

the country's industrial belt, but also in manufactured and finished products.

Regional inequality in China is bound to keep widening as long as thrust

of the policy of the Chinese government remains development of inland

China as a feeder and provider for the country's coastal region. Investments

need to be made in central and western China not only in the resource

exploitation and processing industries, to cater to the demand of the

export-oriented eastern region, but also in sectors from where ready-to-export-products

can be manufactured, ridding the economy of inland China of its dependence

on how China's coastal economy performs. Also, the government has to monitor

the flow of resources into the backward regions so that agriculture does

not get neglected and sufficient investment flows into the agricultural

sector. Food security of the people of inland China cannot be compromised

in the pursuit of industrial growth.