When Vietnam

signed a bilateral trade agreement with the US in 2000 with huge optimism

on the Vietnamese side, probably non one had seriously considered the

possibility that trade between these countries had the chance of becoming

less free in the years to come. This possibility was realized in July

this year, when the US Department of Commerce and the International Trade

Commission agreed to slap anti-dumping duties of up to 64% on Vietnam

exports of catfish to America on the grounds of dumping. This puts in

jeopardy the livelihood of a large number of catfish farmers in the Mekong

Delta in Vietnam. More important, this casts a cloud over Vietnam's huge

shrimp exports to America, exports that a much larger chunk of the Vietnamese

population is dependent on.

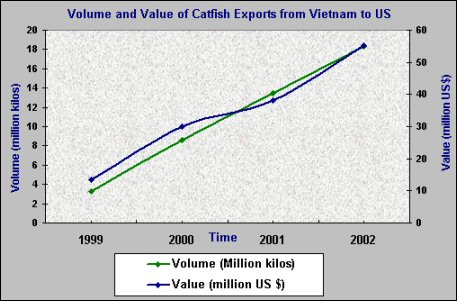

Vietnam had been exporting catfish even before 1995, when the official

embargo on Vietnamese exports was lifted by the US. However, the tremendous

spurt in exports came in 1999 when raw seafood tariffs dropped to zero.

At present, Vietnam exports some 18.3 million kilos of Catfish to the

US, which is valued at 55.1 million $US (2002). The value of exports has

been increasing at the amazing annual rate of 60.21% between 1999 and

2002. The volume of exports shows an even higher growth rate of 77% between

1999 and 2002. The change, which had started to take place from 1999,

shows an incredible increase of over 160% per cent in 2000 when compared

to the 1999 level of trade volume. The value of exports too showed a remarkable,

though lesser, increase of 123.9 % between 1999 and 2000. This trend has

evidently continued since Vietnam's exports have been boosted by a demand

for its tasty, and cheap catfish.

Since tariffs dropped to zero, Vietnam

had been able to export at its normal price, which comes out to be much

cheaper than its American counterpart. This is because Vietnam has the

advantage of cheap labour and other inputs. Raising fish in free flowing

water has the dual advantages of first, producing more tasty fish, and

second, producing fish at much cheaper rates compared to American Catfish

which uses more expensive groundwater. The American Catfish Farmers had

been protesting that Vietnamese Catfish was not produced under hygienic

conditions according to international standards. However, inspection by

the department of Commerce had clearly revealed that this was not indeed

the case. Vietnamese catfish is produced to international standards, and

most of the fish-feed are supplied by an American company called Cargill.

Catfish: To be or not to be

Vietnam's gradually larger presence in the Catfish market soon started

to spell trouble for the 590 million dollars US domestic catfish industry

that is mainly located in Arkansas, Mississippi and a few other southern

states. The trouble had been brewing for some time and a foreboding about

the final pro-protection judgement emerged in 2002 itself, when the Department

of Commerce in the US, in response to a litigation suit filed by the catfish

industry located in the south of US, prevented the Vietnamese catfish

from being called catfish at all. More specifically, the catfish Farmers

of America (CFA) lobbied the Congress to include language in the 2002

Agriculture Appropriations Act that specifically barred Vietnamese exporters

from labeling their fish as catfish. Their argument was that only catfish

of the species 'Ictalurus Punctatus', obviously cultivated by CFA, could

be called catfish. The species cultivated by Vietnam, 'Pangasius', has

now been banned by the American Farm Security Act of 2002.

Vietnamese catfish are now labeled Basa and Tra, which are the local names

for the subspecies. Given the fact that there are actually 2,500 subspecies

in the catfish family, which includes both the American and the Vietnamese

varieties, it was not clear why American Congress believed their farmers

have some intrinsic right to the name catfish that is ranked above the

rights of Vietnamese catfish farmers. But in a world where bigger fish

eats smaller fish, it was not surprising that Vietnamese farmers were

forced to swallow this piece of protectionism and hope for the best. As

it turned out, the demand for Vietnamese catfish, after initially suffering

a decline, picked up again. This was despite active campaigning by the

CFA against it.

Though Vietnam increased its sales drastically since 1999, it had occupied

less than 4% of the total catfish market in America over this period.

However, the bone of contention was the export of frozen Basa and Tra

fillet, which had occupied about 20% of the domestic market in the US.

The American producers are facing competition from Vietnam, the only other

big producer of catfish in the world, in other markets like the EU, Australia

and Japan as well. So it was getting more and more urgent for them to

protect their domestic market.

Anti Dumping: no hope for a non-market economy

The American products continued to suffer from stiff Vietnamese competition.

This made the CFA, think of other measures to escape from it. The next

best method was to suggest a re-course to the provision of anti-dumping

in the WTO rules and push for anti dumping/countervailing tariffs against

Vietnamese catfish. However, it was difficult to prove that the Vietnamese

catfish industry was receiving government subsidies or that the producing/exporting

units were undercutting their export price, which was necessary for proving

that dumping was taking place.

This made it imperative for the CFA to chose another line of offense.

Vietnam, given its historical background, lay vulnerable in one particular

area – its market economy status. It was, as it turned out, easy for the

CFA to argue that Vietnam is a 'non-market' economy. This clause in the

WTO rules, basically suggests that any economy that falls under this category

cannot claim to have competitive market prices. More specifically, their

prices may include an involuntary subsidization given the fact that input

prices (for example of labour) may not be competitively determined.

In this case, the price level of some other market economy, which has

a close resemblance to the non-market economy in question, is used as

a surrogate or proxy for determining whether prices at which products

were offered for sale by the non-market economy, are competitive or not.

This means for example, that for calculating Vietnam's competitive price

level (prices that would have prevailed under a market economy) prices

in some other country that produces similar products under similar conditions

would be used as indicators. Anti-dumping measures could be resorted to

if it was found that these proxy prices (adjusted according to other supply

conditions in Vietnam) reigned above the actual non-market economy prices

offered by Vietnam.

After determined petitioning by CFA and individual American catfish farmers,

the Department of Commerce's import administration determined on November

2002 that Vietnam was to be treated as a non-market economy (effective

from July 1, 2001) under the U.S. antidumping and countervailing duty

laws. To quote from the report, "while Vietnam has made significant

progress on a number of reforms, the Department's analysis indicates that

Vietnam has not yet made the transition to a market economy. Until revoked,

Vietnam's non-market economy status will apply to all future administrative

proceedings covering periods of investigation or review that fall after

the effective date of this decision".

This left the way open for finding a 'suitable' proxy. The Department

of Commerce (DoC) chose to pick India and Bangladesh as surrogate economies

for comparing catfish price levels. The DoC, found the price levels in

these countries much higher than Vietnam levels. Despite protests by the

Vietnamese Association of Seafood Exporters and Producers (VASEP), the

Department of Commerce (DoC) concluded in its preliminary order on January

27th, 2003 that " Vietnamese producers/exporters have made sales

to U.S. customers at less than fair value" and recommended the slapping

of anti-dumping duties on all major producers' products of fish fillets

. They calculated anti dumping margins ranging from 37.94 % (Vinh Hoan

Company) and 63.88% (Vietnam-wide). Subject to a final recommendation

by the DoC, and its approval by the US International Trade Commission

(ITC), America was all set to slap huge anti dumping duties on Vietmnam's

catfish fillet.

Preliminary Antidumping Margins Found by DOC

|

| Company |

Margins |

| Agifish |

61.88% |

| Cataco |

41.06% |

| Nam Viet |

37.94% |

Respondents who

voluntarily

submitted Section A responses

|

49.16% |

| Vietnam-Wide |

63.88% |

Source:

Fact sheet on Preliminary determination in the Anti-dumping

Duty Investigation of Certain Frozen Fish Fillets from

Vietnam, Department of Commerce, USA, 27th January 2003. |

|

The subsequent final recommendation by

Doc on 17th June, upheld more or less its previous recommendation that

Vietnam had been selling its Catfish 'at less than fair value'. Taking

Bangladesh as the surrogate country, the report suggested anti dumping

duties to the tune of 64% be imposed on Vietnam-wide catfish products

with immediate effect. In case of some particular companies that had argued

various critical circumstances, DoC made certain exceptions and applied

different margins, some lower compared to the previous margins calculated

by the preliminary findings. According to this final determination the

Vietnam-wide rate of an incredibly high 63.88% applied to all entries

of the merchandise under investigation except for entries from Agifish,

Vinh Hoan, Nam Viet, CATACO, Afiex, Cafatex, Da Nang, Mekonimex, QVD,

Viet Hai and Vinh Long.

Final

Weighted Average Dumping Margins on Certain

Frozen Fish Fillets from Vietnam |

Producer

/ Manufacturer / Exporter |

Weighted-Average

Margin (%) |

Agifish |

44.76 |

Vinh

Hoan |

36.84 |

Nam

Viet |

52.90 |

Cataco

|

44.66 |

Afiex

|

44.66 |

Cafatex |

44.66 |

Da

Nang |

44.66 |

Mekonimex |

44.66 |

QVD |

44.66 |

Viet

Hai |

44.66 |

Vinh

Long |

44.66 |

Vietnam

Wide Rate |

63.88 |

|

|

Source:

Notice of Final Antidumping Duty Determination of Sales

at

Less Than Fair Value and Affirmative Critical Circumstances:

Certain

Frozen Fish Fillets from the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,

US Department of Commerce, June 17th, 2003 |

|

The ITC, the highest authority within

the US government on international trade issues, subsequently approved

this final determination on July 23rd, 2003. Since domestic legislation

on anti dumping or protectionist laws regulating product standard rules

overrides bilateral trade agreements, the BTA between the two countries

is unable to give any reprieve or confer any free trade advantages to

Vietnam in this case. This however, puts into question the usefulness

of such bilateral trade pacts between two countries that is supposed to

offer mutual benefits to the signatories. If worst comes to worst, it

might start off a trade war between the two. However in that eventuality,

as is the fate of developing countries, Vietnam has much more to lose

than its 'free-trade' partner.

Throughout the process, there were many protests by VASEP to the charges.

The first of these was that Vietnam should not be considered a non-market

economy. More importantly, Indian and Bangladesh prices do not properly

reflect the price situation in Vietnam. Even more unfair, pointed out

VASEP, was the fact that DoC used retail prices as a surrogate for wholesale

prices in Vietnam. In addition, since the Vietnamese farmers were using

American produced fish feed, that component of costs, a major one, could

hardly be underestimated. Add to that the fact that no company in Vietnam

nor the Vietnamese government was in the financial position to be able

to subsidize their exports, either for a significant amount of time or

a major quantity of products.

VASEP denounced the decision on catfish, saying it showed how "a

small group of fillet breeders in some southern states of the U.S. can

put pressure on American authorities" to ignore the principles of

competition and free trade it preaches worldwide. But this did not change

the decision of the DoC or the ITC. However, apparently the ITC did find

that some miscalculation had taken place in calculation of the 63.88%

margin and will probably re-calculate the dumping margin. But this is

likely to be a minor change in the duty figure(s) and not a major shift

in policy.

Shrimps: Another Victim in the Wings?

This is just the beginning of Vietnam's worries. Further problems plague

the seafood industry, the third highest export, in Vietnam. After the

successful campaign against Vietnamese catfish, shrimps seem the obvious

next target. US Shrimpers, especially from the Louisiana state that contributes

40% of the total shrimp production of the country, are all set to follow

the example of catfish. They claim that pond raised cheap shrimp from

Vietnam and other Asian and Latin American countries are flooding the

American market and driving shrimp prices to the floor. The tentative

list of countries to be targeted comprise of 16 countries including Brazil,

China, Ecuador, India, Thailand and Vietnam.

For Vietnam, this would bring even deeper trouble than the catfish tariffs.

Shrimp is the third highest export after crude oil and textiles and contributes

the highest share of its seafood exports. The US is also its largest market

as figures for 2002 show. Valued at 467 million US$, exports to the US

accounts for 48% of Vietnamese seafood exports. A huge number of farmers

in Vietnam are dependent on shrimp production and exports. It affects

the whole of the country rather than a specific region as in the case

of catfish. The fact that Vietnam has already been tagged a non-market

economy, makes it even more vulnerable compared to other countries in

the 'offenders' list. Further, being poor and small, its ability to defend

itself is much lower compared to countries like Brazil, China and India.

In the case of shrimp, however, there are two factors that Vietnam might

be able to make use of. First, the issue is much larger here and involves

many big countries in the developing world. Therefore, any protectionist

move on part of the US may land this dispute before the WTO. Even though

Vietnam is not yet a member of WTO, if the US is prevented from imposing

anti dumping tariffs on its member countries it should lose the moral

justification to carry forward a similar anti dumping suit against Vietnam.

However, the record of US morals, especially in trade negotiations, has

not been very strong. But there is another more material problem that

may arise for the US shrimp farmers. Since shrimp has a huge market in

America, slapping anti dumping duties that raise the price of shrimps

in the American domestic market may urge the large consumer base to actively

oppose any such attempts. This should be a matter of some concern for

the Department of Commerce.

Conclusion

The issue now affects the very poor catfish farmers of Vietnam in the

Mekong Delta and may in future affect the whole country. Fish farmers

in Vietnam are generally poor and operate on a very small scale. Apart

from desperately needing good sales for making ends meet, many have the

additional problem of paying off old production debts. Many poor farmers

had already mortgaged their land for buying fish cages. Shrimp farmers

are also heavily indebted after investing in drenches and ponds. In addition,

most of the seafood farmers are based in the poorest parts of the country,

where agriculture is not very productive given high soil salinity and

frequent flooding of agricultural land.

The protectionist antics of a country that prides itself on pushing trade

openness has unfairly robbed Vietnam's seafood farmers of the opportunity

to come out of indebtedness and make a decent living on the basis of hard

work. It also robs them of the advantage to make profitable use of their

natural resources. In addition, this is one of only a few cases where

low labour costs (and low opportunity cost of labour) can actually confer

certain advantages, at least in part, to the poor in developing economies.

This is so because the farmers themselves are very poor and also use a

lot of family labour. But this is evidently not so in a system of free

trade that is propagated by the US. Moreover, the fact that the Byrd amendment

of US law, entitles companies that initiate such anti-dumping legal suits

to revenues from such anti-dumping duties, is a further affront to the

poor farmers in Vietnam. By a WTO ruling, this amendment is to be repealed

but it would still be in effect till the end of 2003. So the American

farmers are still set to make an additional monetary gain from these duties.

Under the circumstances, Vietnam has no choice but to go on with its seafood

production, diversify both its export products and markets, cross its

fingers and hope for the best! It is an irony that such protectionism

has come from the US whereas the US and the EU are the very powers that

have been intent on prizing open developing economies to free trade. The

US has clearly shown that free trade for the powerful is the freedom to

use every backdoor tactic to ensure that trade is protected according

to the dictates of their own interests.

|