While the annual trade figures released

by the World Trade Organization for 2003 points to strengthening recovery

in global trade and an optimistic outlook on prospects for further trade

expansion,[1] an analysis of medium-term developments

in global trade patterns suggests that even an expanding world trade scenario

may not be as promising or neutral in its implications for the prospects

for developing countries' trade expansion.

The medium-term developments in global trade provided in a report that

forms part of a broader WTO annual study titled "World Trade Report

2004", highlights two significant areas in which international trade

patterns have experienced major structural changes at the disaggregated

product level over the past two decades (1985-2003)[2].

Along with the fact that contrary to general perception, growth in services

trade no longer outstrips that in goods, there is a shift in agricultural

trade to processed products, away from commodities.

It is argued in this review that these structural shifts would have critical

implications for the prospects of developing and less developed countries

to expand their market shares in world trade. The first section will give

a brief overview of the global trade trends in 2003, following which the

structural shifts in services and agricultural trade patterns are examined

for their implications.

Trade Trends in 2003

According to the annual trade figures released by the World Trade Organization,

despite being one of the more disruptive years in recent times, 2003 proved

a good year for the world economy. A 2.5% increase in global output, propelled

mainly by higher than expected economic growth in Asia and the United

States, spurred world trade to recover by an average real increase of

4.5% in 2003. This was stronger than expected a year ago after the outbreak

of SARS and the US-led war in Iraq in early 2003. In addition to the fact

that this strengthens the global trade recovery in 2002 from the sharp

decline in the preceding year, the projection is that 2004 also looks

promising for further trade expansion[3].These

annual estimates from the WTO offer an optimistic outlook on world trade

prospects.

Trade growth exceeded output growth by an atypically small margin in 2003

when compared to the 1990s, when average trade expansion was 6.5%, approximately

twice as fast as merchandise output growth. It is partly because of the

end of the information technology sector boom which was the most dynamic

segment in world trade over the 1990s, that the typical excess of trade

over output growth was unusually small in 2002 and 2003. However, as in

2002, trade acceleration in 2003 was much stronger in dollar values than

in real terms[4].

The nominal value of world merchandise exports rose by as much as 16%

to $7.3 trillion and commercial services exports expanded by 12% to $1.8

trillion in 2003. Both these were the strongest annual increase in nominal

terms since 1995.

This difference between the nominal and real trade growth rates reflected

the major role played by exchange rate changes and commodity price rises

in inflating dollar trade values. For the first time since 1995, dollar

prices increased for both agricultural and manufactured products in 2003.

It is estimated that on the global average, prices of manufactured goods

rose by nearly 10 per cent, the first annual increase since 1995. Similarly,

fuel prices were up by 16 per cent, boosted by temporary supply shortfalls

linked to the conflict in the Middle East and civil unrest in Venezuela,

as well as due to increased oil demand from the US and a booming Chinese

economy. On average, the prices of non-fuel commodities also rose by 7

per cent on spot markets, including a 12% increase in metal prices.

The combined effect of these price rises and exchange rate changes involving

dollar depreciation against major currencies led to a 10.5% strengthening

of world merchandise trade prices in 2003. Thus, the large increase registered

by merchandise trade in nominal terms was a reflection of this.

Meanwhile, commercial services trade, which accounts for about one-fifth

of world trade in goods and services, also expanded by 12% in 2003. Even

though this was the strongest increase since 1995, services grew less

rapidly than merchandise trade in 2003 in contrast to the preceding two

years (2001 and 2002).

The influence of price and exchange rate effects on nominal merchandise

trade differed sharply by region, depending upon the sectoral distribution

of exports as well as the exchange rate regimes adopted by the various

economies. In general, nominal export growth in excess of 20 per cent

was recorded by many oil exporting countries (e.g. Russia and Saudi Arabia)

and in countries with strongly appreciating currencies, in particular

in Western Europe. Two thirds of the nominal rise in the Middle East's

exports was accounted for by higher oil prices. In Africa too, merchandise

exports of oil exporters (and South Africa) expanded at a greater rate

than the majority of non-oil exporting countries. But, while the share

of Africa in world merchandise exports increased in 2003, at 2.3% it remained

below the level recorded ten years ago.

Exchange rate changes had the most significant influence on trade values

in the case of Western Europe. Despite a near stagnation in volume terms,

there was a 17% increase in Western Europe's merchandise dollar export

value. This was almost entirely due to the price effects of the strength

of the euro and other European currencies vis-à-vis the US dollar,

as its trade in fact reported a small decrease when measured in euro terms.

For the third year in a row, the transition economies recorded the greatest

merchandise output and trade growth of all regions in 2003, facilitated

by a combination of strong currencies, higher fuel prices, strong regional

demand (including from Russia), and rising FDI inflows due to their deepening

westward integration.

The lowest export growth in dollar values was reported for North America

and Lain America. Interestingly, after the stagnant growth in 2002, Latin

America's exports rose by 4.5%, sustained mainly by a recovery in demand

for primary products from Asia.

Asia is the only region where price changes accounted for less than one-third

of the increase in dollar value of the region's merchandise exports. Significantly,

Asia's merchandise trade was driven strongly by the expansion not only

of China's trade, but also intra-Asian trade. With its imports growing

at 40% and exports at 35% in nominal dollar terms, China's trade expansion

was unprecedented for a country with such substantial trade volume. Its

export and import expansion was most outstanding particularly in office

machinery and telecom equipment segment.

Although more detailed data, especially on intra-Asian trade, is required

for making conclusive observations, the above trend points towards the

increased integration of China into the electronics sector production

networks, regionally and internationally. The large flow of capital goods

to China highlighted by the report as financed by strong FDI inflows related

to the relocation of manufacturing assembly operations and the recovery

in the electronics industry, does appear to support this observation.

In fact, this in itself may explain the large expansion in intra-Asian

trade. For example, according to the WTO, the higher than regional average

trade growth recorded by the Republic of Korea was owing to a sharp rise

in its exports to China linked to the recovery of the IT sector. The accelerated

growth in Asia's largest economies driven by a recovery in the electronics

and IT sectors thus may have provided a major stimulus to regional trade

expansion. In addition, the 2.7% GDP growth in Japan after years of recession

also contributed to the momentum in Asian trade.

Meanwhile, for the first time, China's imports exceeded those of Japan,

and China currently ranks number three among the world's leading merchandise

importers. The increased and heavy dependence on Chinese economic expansion

that this implies for sustaining global trade growth has serious implications

for world economic growth prospects.

Additionally, for the third successive year, United States import growth

exceeded the world average and continued to be a significant factor in

mitigating sluggish world trade growth. Thus, the fact that US import

growth continues to exceed export growth, widening its trade deficit further,

also continues to be a factor causing uncertainty about the sustainability

of world trade growth.

While all regions recorded stronger nominal export and import growth in

2003 compared to 2002 in the case of merchandise trade, in services trade,

Asia's exports are estimated to have expanded at a lower rate than in

2002. While Asia and Latin America's export expansion was limited to 6

per cent, Western Europe and the transition economies recorded annual

gains ranging from 16 per cent to 21 per cent boosted by the strength

of their currencies vis-à-vis the dollar. Thus, gains in the ranking

of the leading commercial services traders in 2003 were recorded principally

by West European countries and transition economies at the expense of

American and Asian countries.

Clearly, the annual data for 2003 was impacted by temporary and cyclical

factors which tend to affect a single year's data. Thus, shifting the

focus towards medium-term structural changes at the disaggregated product

level, we can better decipher the underlying structural pattern influencing

these trends.

Structural Shifts in Global Trade: Medium-term Trends

in Manufacturing and Services Trade

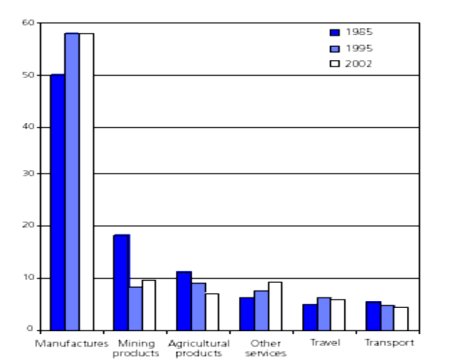

A summary of world trade developments by six broad sectors for the period

1985-2002 as provided in the WTO report of June is reproduced in the Chart

below. As this report points out, while at the aggregate level services

and merchandise trade growth have evolved in a roughly similar way since

1990, developments are more varied at a disaggregated level.

It reveals that since 1985, transport services as well as agricultural

and mining products among merchandise product groups expanded less rapidly

than world trade. Thus, while the share of the travel category rose between

1985 and 1995, it decreased thereafter. In contrast, trade in manufactured

goods and the "other" services category was more dynamic, showing

steadily increasing shares over the period. Among all product and services

categories, the share of mining products shows the biggest variations

owing to the impact of fluctuating oil prices throughout the 1985-2002

period.

Thus, overall, there is no indication that services categories in general

have increased their share in international trade and the latter continues

to be dominated by manufactured products to the extent of 75%. This implies

that manufacturing sector capabilities will strongly dominate the prospects

of developing and less developed countries' ability to increase their

shares in global trade.

A further breakdown of the fast growing world exports of manufactured

goods however reveals that the most dynamic product subcategory by far

has been office and telecom equipment, which expanded at twice the rate

observed for total manufactured goods in the 1990s. Consequently, its

share gained five percentage points between 1990 and 2000 and accounted

for 12.1 per cent of world merchandise and services exports. In fact,

the gains of this group exceeded the gains made by all manufactured goods

combined. Even though the crisis in the IT sector in 2000 arrested this

trend and the share of the sector in total manufactures has stagnated

since then, it continues to be one of the three largest manufactured export

segments, along with other machinery and equipment as well as chemicals.

Among the other subcategories of manufactured goods, iron and steel products

and textiles products recorded below average trade growth in the 1990s,

and showed a significant decline in their share in world trade over the

1990-2002 period.

These trends clearly point towards rising concentration of global trade

not only in manufactured products, but within manufacturing into an increasingly

narrow range of products such as machinery and equipment and chemicals.

Chart: Share of major goods and services categories

in world exports (a), 1985-2002.

(Percentage)

|

|

a Goods and commercial

services exports combined. |

Source: WTO, International

Trade Statistics, 2003. |

However, import liberalisation that has been occurring in the manufactured

sector through tariff reduction under the non-agricultural market access

(NAMA) negotiations, and restrictions on industrial policy options brought

in through trade-related investment measures (TRIMs) have been rapidly

eroding the South's capability to establish indigenously founded export-oriented

manufacturing sectors, which can withstand shifts in competitive advantages.

Further, the pattern of global foreign direct investment (FDI) shows that

machinery & equipment and chemicals industries have also been the

largest FDI recipients throughout the 1990s. This means that most of the

benefits of the dynamism in world trade in manufactures will be appropriated

by the MNC firms involved in the world-wide manufacturing sector production

networks.

The trends provided by the report regarding services trade also suggest

gloomy prospects for the South, despite alluring promises being made in

services trade negotiations under the GATS, regarding the opportunities

for developing countries to expand their export revenues through services

exports.

In 2003, commercial service exports as a whole was dominated by the US,

UK, Germany, France, Japan and other West European countries. In fact,

Western Europe alone constitutes about one half of world commercial services

exports. Among the select few developing countries which had a presence

among the top 30 leading commercial services exporters' list last year,

only China and Hong Kong accounted for shares of 2.5% each in the total.

The others such as South Korea, Singapore, India, Greece, Taiwan Province of China, Turkey,

Russia, Thailand, Malaysia and Mexico all had shares ranging only between

2% to 0.7%.

At the same time, a larger number of developing countries were present

among the top 30 leading importers of services in 2003. Even for China,

which has emerged as the largest services exporter among developing countries,

imports of commercial services continued to exceed its exports in 2003.

Only Hong Kong recorded a significant net surplus in services trade, while

Singapore and India also recorded some minor surplus in 2003. In general,

net gains from trade in services appear to be in the deficit for the large

majority of even leading developing country service exporters. The reason

behind this may be found in the medium-term trends in commercial services

trade.

Even though detailed statistics on commercial services trade are not yet

systematically available, on the basis of a sample of large services traders,

the report indicates a few sub-categories of international services trade

which report outstandingly strong export growth between 1995 and 2002.

These subcategories comprise (in descending order of their estimated growth

rate) computer and information services, financial services, insurance,

personal, cultural, and recreational services; and royalties and licence

fees[5].

It can be seen that almost all of these, especially the fastest growing

IT and financial services, are dominated by developed country firms. It

is evident that the level of sophistication required to compete in the

markets for these services will not be within the reach of the majority

of middle and low-income countries.

Thus, if the developing countries succumb to the pressure in the ongoing

GATS negotiations, to change the ownership and delivery of services in

their countries through its massive deregulation and privatization agenda

covering the entire scope of services, it will only help the developed

country transnational corporations to secure an expansion in their already

dominant global market share for services.

Medium-term Developments in Aggregate Agricultural

Trade

Even more disturbing long-term trends emerge from the WTO report in the

case of global agricultural trade. First of all, even as agricultural

trade remains very important for many countries, the share of agricultural

trade in world trade has decreased steadily in the longer term. Secondly,

processed agricultural products have been a more dynamic component of

international agricultural trade in the 1990s than unprocessed and semi-processed

goods.

There are several inter-related aspects of agricultural trade which are

brought out in the report. Most significantly, the significance of trade

in the agricultural sector has increased tremendously across the globe.

The volume growth of world agricultural trade during 1990-2002 was close

to 4 per cent annually, which was roughly twice that of agricultural production.

Real trade growth in agriculture during 1990-2002 in fact exceeded that

over the 1973-1990 period (2.4 per cent). It is clear that this points

to the increasing role of trade in agricultural sector at the global level.

However, despite this faster growth when compared to the earlier period,

since growth in agricultural trade was less strong than total merchandise

trade in nominal terms between 1990 and 2002, its share in total merchandise

trade has decreased from 29 per cent in 1963 to as low as 9.3 per cent

in 2002 [6]. The steadily

declining share of agricultural products in merchandise exports in the

1990s could be observed in most regions. The share of agricultural products

in intra-developing country trade also decreased from 15.5 per cent in

1990 to 10.7 per cent in 2002. Thus, even as the importance of trade in

the agricultural sector has increased and agricultural trade remains very

important for many countries, the share of agricultural trade in world

trade has decreased steadily in the longer term.

While the report does not offer any explanation for these seemingly conflicting

trends, clearly, the erosion of agriculture products' share in total merchandise

trade when agricultural trade was expanding in real terms reflects the

steady terms-of-trade decline experienced by agricultural commodities

over the last several decades[7]. The impact

of this has been the most severe for those countries which are dominant

suppliers of these products globally.

But, even so, agricultural products remain, for many countries, the mainstay

of their merchandise exports. In recent years (1999-2001), agricultural

exports accounted for more than one quarter of total merchandise exports

in more than 55 countries (developed and developing) and still exceeded

one half of total merchandise exports for 32 countries.

There were no significant changes in the regional shares of global agricultural

trade during 1990-2002. While Western Europe's and North America's share

in world exports of agricultural products each recorded a decline of two

to three percentage points, the combined share of Australia and New Zealand

at 4.5 per cent in 2002, remained unchanged compared to 1990. For the

developing countries as a group, the share amounted to 30 per cent in

2002 compared to 27 per cent in 1990. However, this increase in the share

of developing countries was mainly restricted to the Latin American and

transition economies, which increased their share by about two percentage

points between 1990 and 2002. Developing Asia recorded only marginal gains

over the entire period, whereas the share of Africa declined slightly.

Also, the increase seen in the share of developing countries could be

just due to the impact of the recovery in agricultural commodity prices

in 2003 from the decline since 1995, which may have led to slight improvements

in the shares of some of the agricultural exporting developing and low

income countries. But, this could not be ascertained from the information

available in the current report. Accounting for about 70%, developed countries

dominated global agricultural trade in 2002.

However, the report does point out that the share of intra-developing

country trade in developing country agricultural exports has increased

significantly from 31 per cent in 1990 to as much as 43 per cent in 2002.

At the same time, interestingly, the share of intra-developing country

trade in developing country imports of agricultural products was even

larger than that in the case of exports. In 2002, nearly one half (47.6%)

of developing country agricultural imports originated from other developing

countries.

These trends inevitably lead us to conclude that for developing country

agricultural exports, the developed country markets have clearly become

less accessible than those in developing countries, despite the fact that

WTO negotiations have been bringing about tariff liberalisation in agricultural

trade. But, simultaneously, the fact that there has been a steady rise

in the commercialisation of agricultural production globally, dominated

by transnational agribusiness firms, could also be behind this rapid rise

in intra-developing country agricultural trade.

It has been observed that the concentration in the international food

processing and food manufacturing industries has increased tremendously

over time and that these industries have moved from being more or less

competitive, to being oligopolistic or monopolistic in nature. Companies

which were engaged in one stage of the food system have either diversified

into other stages of the food system or have forged strategic allegiances

through mergers, partnerships and acquisitions. For instance, companies

such as Cargill, Monsanto in foodgrains and Tyson Foods in livestock not

only grow crops and rear livestock, but also process and manufacture food

products which they finally sell to the retailers. By integrating all

the stages of the food system, such companies have come to own the products

from the farm to the shelf [8].These changes

in the way agricultural production and trade are organised around the

world could also be the underlying factor behind the other major structural

change in agricultural trade highlighted by the WTO report.

Structural Shifts in Global Agricultural Trade

When agricultural trade between 1990 and 2002 was analysed by their stage

of processing (or value-added content), it was found that exports of processed

agricultural products expanded significantly faster than those of semi-processed

and unprocessed agricultural products. The share of processed products

showed a clear upward trend throughout the 1990s, rising from 42 per cent

in 1990-91 to 48 per cent of global agricultural trade in 2001-02.

The data revealed that trade in beverages (which are considered 100 per

cent processed) recorded an above average expansion in the 1990-2002 period

(4.8 per cent annually), while natural fibres and hides and skins (which

are considered 100 per cent unprocessed) recorded an absolute decrease

or near stagnation in the observed period. In eight other categories (with

the potential to move from unprocessed and semi-processed to processed

goods), there was a marked shift to more processed goods within the group

(cereals and products, coffee, tea, cocoa and spices, fish, other foodstuff,

meat and live animals, other agricultural goods (including cut flowers),

tobacco and sugar and sugar products. A moderate decrease or stable share

of processed goods was observed for the remaining categories (dairy products,

eggs, fruits, vegetables and nuts and oilseeds, cakes and vegetable oil).

The report reveals that about three quarters of the countries for which

data was available in the UN Comtrade database recorded an increase in

the share of processed goods in their agricultural trade between 1990-91

and 2001-02. In fact, there was a marked increase in the share of processed

products in total agricultural exports for the 14 major global exporters,

with the exception of two Latin American countries (Brazil and Chile).

The largest shifts to more processed agricultural products could be observed

in Asian developing countries (China, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand,

with gains in shares of processed over unprocessed agricultural exports

of 14, 17, 28 and 11 percentage points respectively). Marked increases

could also be observed for Canada and Mexico. Agricultural exports of

developing countries to high-income markets also experienced this structural

change.

Based on this, the report summarises that there has been a broad-based

shift across countries towards processed agricultural products, which

have been a more dynamic component of international agricultural trade

in the 1990s than unprocessed and semi-processed goods. The conclusion

appears to be that most countries have and would benefit from this structural

shift. However, the real picture may be more complicated than what the

report appears to suggest.

Based on trends in two lower income countries, Bolivia and Peru, which

have a higher share of processed goods in their agricultural exports than

New Zealand, the report suggests that there is no strong overall link

in the sample between income levels and the share of processed agricultural

products. But, it then contradicts this by adding that in general all

countries with a very low share of processed goods in their agricultural

exports (15 per cent or less) are indeed low or low middle-income countries

(e.g. Cameroon, Ethiopia, Honduras, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Uganda and Zimbabwe).

On the contrary, one of the major implications of the fact that processed

goods have become the more dynamic category of agricultural trade would

be its impact on the trade expansion capacity of developing and low income

agricultural commodity exporting countries. Based on the singular example

of Chile which managed to expand agricultural trade between 1990-2001

across all product categories and stages of processing, the WTO report

claims that the above structural shift does not imply that individual

countries cannot achieve high export growth in unprocessed and semi-processed

goods. Chile's outstanding export expansion in agricultural products would

clearly need a deeper investigation to understand in particular whether

it was related to any free trade agreements in operation.

But, as the report itself points out in the concluding paragraph, with

respect to agricultural exports of low-income countries, no shift towards

an increased share of processed goods could be observed in any of the

three major higher income markets. Thus, there seems to be an attempt

to underplay the possible unfavourable outcomes that this structural shift

in agricultural trade may bring about.

According to the WTO report, the two factors that favour the expansion

of processed goods over unprocessed goods are the following. First, processed

goods have a larger potential for intra-industry trade and offer more

possibilities for product differentiation than unprocessed goods. The

example offered is that cocoa-producing countries will not see much bilateral

trade in cocoa beans, for example, while chocolate-bar/snack producing

countries can exchange their products, satisfying a broad variety of different

tastes. As per capita income levels increase, consumers appreciate a larger

variety of similar products and increasingly buy goods with a brand label.

Secondly, the potential to increase value added for a given consumer food

product is, in general, far larger than for unprocessed foods and this

underlies the shift to increased trade in processed foods. Also, the trend

to smaller household size and an increase in participation by women in

the labour force strengthens consumption trends towards more processed

food at the expense of unprocessed food. In fact, this is confirmed by

the trend on the import side, which showed an even more striking increase

towards a higher share of processed goods. Among the 38 major agricultural

importers, only eight recorded a decrease in the share of processed goods

[9].

It is evident that with processed goods becoming the more dynamic segment

within agricultural trade globally, for the middle and low income agricultural

exporters to expand their export revenues from agricultural trade, they

would have to first of all participate in this dynamism. However, the

value addition and product differentiation required for being successful

exporters in the processed segment calls for production process capabilities,

which the report appears to take for granted, but which are largely beyond

the reach of the indigenous farming communities in such countries. This

implies that manufacturing sector capabilities will strongly dominate

the prospects of developing and less developed countries' ability to increase

their shares in global agricultural trade.

Ironically, the logic offered for advocating tariff escalation to developing

countries is that progressively higher tariffs on higher stages of processing

than for agricultural commodities will promote their shift to higher value

added agricultural products. However, by being forced to undertake rapid

tariff liberalisation of their lower-end primary products, these countries'

very base for generating the surplus revenues required for investment

in higher value-added processing segments is getting eroded. Many low

income countries are being pushed into cutting their agricultural input

subsidies, promote commercial export-oriented agricultural production,

and reduce their agricultural tariffs all at the same time, as conditions

for multilateral loans. These policy prescriptions, for instance, find

their place in the so-called country papers, or the Poverty Reduction

Strategy Papers (PRSPs).

That is, while developed country agricultural exporters enjoy high subsidies,

their developing country partners are being forced to reduce subsidies.

Further, even as the tariff reduction imposed upon the developing and

less developed countries exposes their farmers to competition from the

highly subsidized farm production in the developed world, actual market

access provided by developed countries for developing country agricultural

exports remain immensely low, because of the high tariffs and quotas and

the prevalence of domestic support and export subsidies given by the EU

and the US. Thus, the ability of low and middle-income agricultural producers

to upgrade themselves to break into the global markets dominated by the

increasingly integrated production and trading networks of transnational

agribusiness firms on their own is highly limited.

Therefore, proliferation of agricultural trade which pushes commercialised

agricultural production on the one hand and refuse meaningful market access

on the other hand is happening at one level. Thus, most of the benefits

of the dynamism in trade in processed agricultural products will be appropriated

by the MNC firms involved in the global agri-food value chain. At another

level, there is increasing food import dependence because of agricultural

trade liberalisation by developing countries. These simultaneous processes

will lead to the break-down of the self-sustaining agricultural production

systems that have been the traditional backbone of middle and low income

countries' farming communities.

This will have severe human development implications, food security being

central to them. The fact that the rise in commercialisation of agricultural

activities is corresponding with a period of increasing global poverty

levels and decreasing per capita food consumption in several countries,

as has been highlighted by many agricultural economists, in fact portends

the impending development crisis facing the South.