John Stuart Mill was among the foremost liberal thinkers of modern times who wrote extensively…

Are Global Oil prices the culprit for India’s burgeoning Trade Deficit? C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

India’s external account has once again emerged as a source of concern, as the current account deficit widened to reach 2.4 per cent of GDP over April-June 2018. This increase was driven entirely by the trade deficit, which grew rapidly in 2017-18. Since 2014, as Figure 1 shows, exports have been mostly stagnant (after a period of healthy increases before then) but total imports came down and then increased sharply in 2017-18. This was reflected in the total merchandise trade deficit, which declined for several years from the large deficit observed in 2013-14, and only rose sharply once again in 2017-18.

More recently, over the period April-November 2018, the trade deficit is once again said to have widened to Rs 892 billion, an increase of 30 per cent over the same period in the previous year.

Figure 1

This timing suggests that global oil prices have been the significant driver of the total trade deficit. After all, India is a substantial net importer of oil. Periods of rising global oil prices have therefore been associated with higher total imports and when global oil prices fall or stay low, the import bill comes down correspondingly. So it seems only natural to assume that the external deficit is really driven by factors outside domestic policy control, particularly the vagaries of the global oil market. Indeed, there is no doubt that the Modi regime benefited hugely from the global decline in oil prices that was so marked in the first four years of its tenure, which reduced the pressure on the balance of trade, contributed to lower rates of domestic inflation, and provided windfall gains to the public coffers as the government did not pass on most of the oil price decline to consumers but instead raised tax rates. .

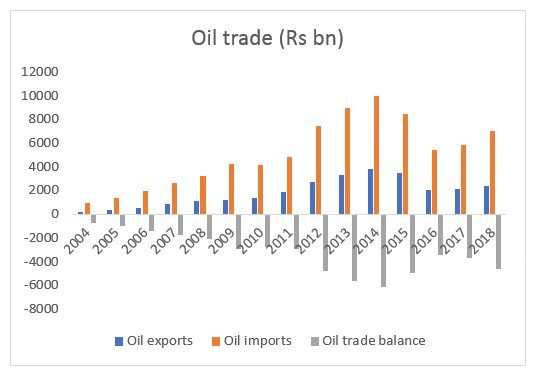

However, matters with respect to the impact of oil prices on the balance of trade are not quite so simple. To start with, India is both and exporter and an importer of petroleum products, and the growing involvement of domestic oil refinery and distribution corporations (particularly the private ones) has made external trade in oil and oil products quite complicated. Quite often, increased oil exports reflect the choices domestic oil companies make to produce for the domestic market or to export, which in turn are related to the local prices and duties, therefore driven by domestic policy. Figure 2, which shows only the oil trade balance, indicates that the oil deficit can increase even in periods of relatively low global oil prices (as in 2016-17) precisely because of such choices made by Indian oil corporations, especially the private players like Reliance.

Figure 2

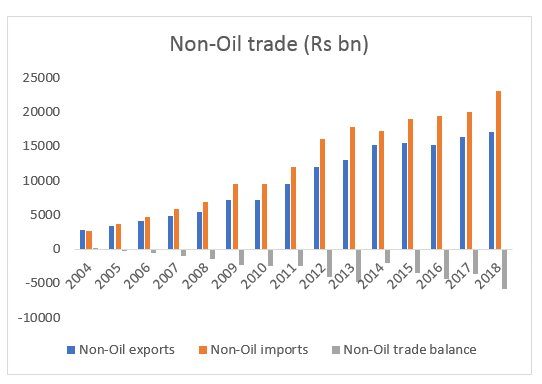

What complicates matters further is the fact that non-oil imports have typically been high and rising rapidly. Figure 3 shows that even in the mid-2000s, non-oil trade was largely in balance and then began to show only relatively small deficits from 2006 onwards. After 2008 such deficits grew rapidly, as imports kept growing much faster than exports. The non-oil merchandise trade deficit peaked in 2012-13, ironically a time when global oil prices were also not that low. They came down the following year, but then rose once more, as non-oil imports kept expanding rapidly.

It is worth noting that this increase was driven by increasing import volumes, as prices for many of India’s imports also remained low. This is an important point, because it points to the fact that the potential of imports to displace domestic production has been much greater than is indicated only by the value of imports. Indeed, increased imports of a variety of final goods, both primary and manufactured, have added to the woes of many small-scale producers in agriculture and industry as they have kept domestic prices of their output low, sometimes even below costs.

Figure 3

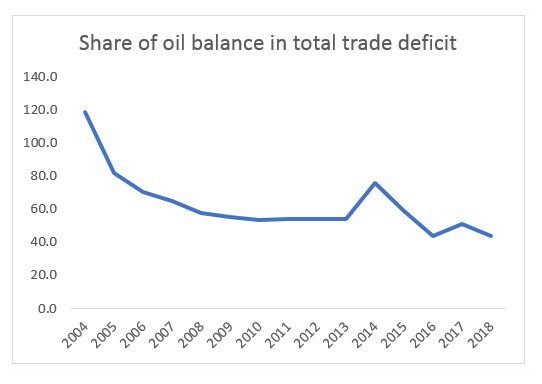

This has also meant that even in the period of rise in oil prices in 2017-18, the non-oil trade deficit was even larger than the oil trade deficit. Figure 4 points to an interesting tendency: since 2004, the share of the oil deficit in the total balance of trade deficit has been coming down continuously, barring the outlier year of 2013-14 when world oil prices spiked sharply. Indeed, from being 20 per cent more than the actual trade deficit (because the non-oil balance was in surplus then) it has fallen to explaining less than half – only 44 per cent of the deficit in 2017-18.

So high global oil prices are only one of the many reasons why India should be concerned about the rising external trade deficit. The more significant culprits lie elsewhere, and they cannot be simplistically blamed on global forces beyond the government’s control.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on January 1, 2019)