Thames Water, one of England’s many regional water monopolies, infamously privatised by Margaret Thatcher in…

The Impasse in External Debt Relief C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

When the pandemic first swept across the globe and destroyed economies in its wake, there were at least some expressions of international solidarity among leaders of the rich countries. External debt problems were widely recognised to be inevitable in the new crisis context; to address them, G20 governments declared a Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) from May 2020, designed to reduce some of the immediate debt repayment burden of the poorest and most vulnerable economies. Yet this and the subsequent “Common Framework for Debt Treatments” of November 2020 barely scratched the surface of the problem, and are unlikely to fend off future likely defaults.

There were several fundamental design flaws in the DSSI, and different but not unrelated flaws as well in the later extended framework, which suggest that G20 leaders are either oblivious to the nature and severity of the problem, or just want to ignore it since it is too complex for them to address.

Take the DSSI, which offered a temporary suspension of debt service payments (both interest and principal) on bilateral sovereign debts, if requested by eligible countries. Eligibility was strictly restricted only to countries that can receive loans from the World Bank’s International Development Association and least developed countries (LDCs) that are current on their International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank (WB) obligations – coming to 76 IDA countries and Angola. But this was only a moratorium, not a standstill, which means that once the period ends, the “beneficiary” countries will have to pay the deferred principal and interest over the three years after a one-year grace period. The period of suspension has recently been extended to the end of 2021, but since the deferral of payments is “net present value neutral”, it does not reduce the total payment debtors will eventually have to make.

This is not even a drop in the ocean of what is required for developing countries. Only bilateral official creditors were included; even multilateral creditors like the IMF and World Bank stayed out, on largely specious grounds. Private creditors were asked to volunteer a similar suspension, but none of them did. Many developing countries in genuine need of debt relief avoided it because the benefits were so meagre, even as availing of the facility would send an adverse signal to financial markets.

Only 46 countries applied for this relatively minor relief (amounting to only $5.3 billion thus far) and would still have to pay US$ 17 billion to multilateral and private lenders during 2021, as a critique by Eurodad makes clear. Indeed, the benefits in 2020 came to only 1.6 per cent of the total debt payments due by developing countries, excluding China, Mexico and Russia.

Furthermore, these 46 countries had to continue to pay $6.94 billion to private creditors. The inability to involve private creditors even in as limited an effort as a moratorium was therefore a major flaw of the initiative. The later attempt at debt restructuring is supposedly meant to involve private creditors, but the mechanism here is so flawed that it is unlikely to have any impact. All it does is require the concerned debtor country to enter into debt restructuring negotiations with private creditors as a precondition for the IMF agreement that must accompany the restructuring. Not only does this put the onus on the debtor country rather than on the creditors, but it forces the country to accept IMF conditionalities that are still heavily skewed in the direction of fiscal austerity and regressive tax measures.

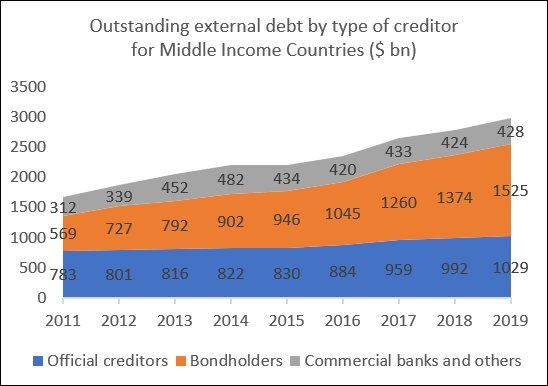

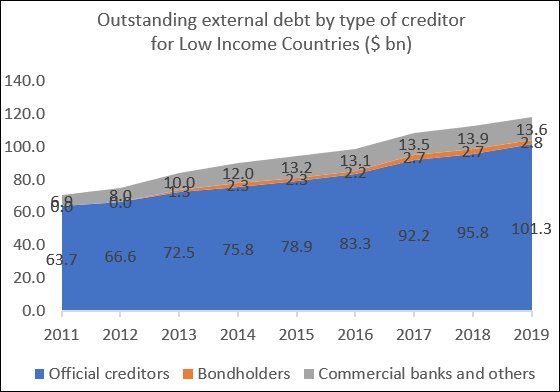

In addition, the greater part of developing country debt that is likely to come under stress has simply been excluded by both initiatives only a small subset of the developing world has been deemed eligible. And among middle income countries that have experienced dramatically increasing levels of external debt over the past decade, the role of private creditors, especially bond holders, has become very significant. (Figure 1) Even among low income countries (Figure 2) private creditors are not entirely absent, although they are much less significant and have grown much less.

Figure 1: Bond holders now dominate among external creditors of middle income countries

Figure 2: There are private creditors even among low income countries

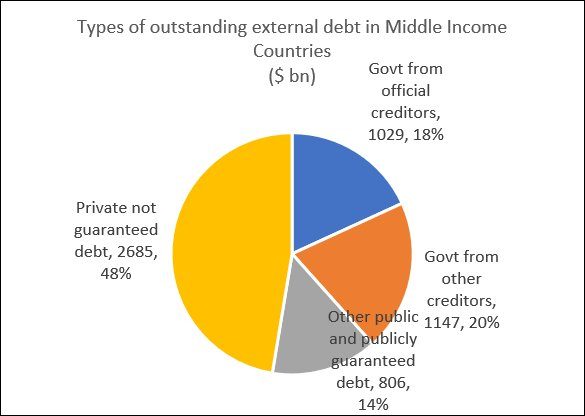

Figure 3: In middle income countries, non-guaranteed private debt is almost as much as public and publicly guaranteed debt

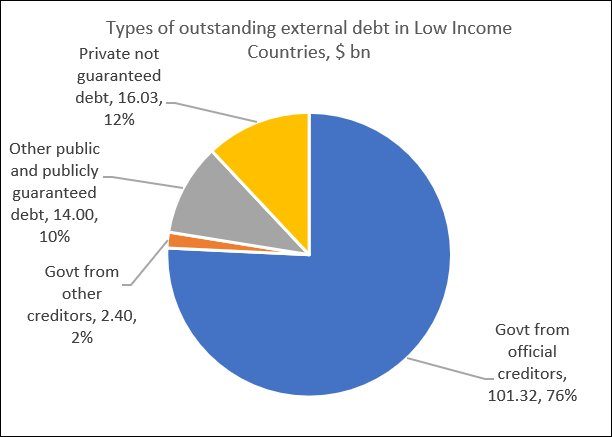

Figure 4: Official creditors still dominate for low income countries

The problem is that many middle income countries are already facing severe debt stress, and several of them are also on the verge of default. The absence of a proper sovereign debt workout mechanism at the international level has been a big problem for decades, but the ack of effective action has meant that the problem has grown beyond control. Collective action clauses in international debt have gone through many iterations, but developing countries typically have many vintages of such debt contracts, so restructuring becomes all the more complex. With bonds, a further problem is that the identification of the actual holders can be a gargantuan task. As noted by another Eurodad report, the obstacles to proper identification of the beneficial owners include “unregistered secondary market transactions, use of custodian and nominee accounts, off-market transactions, repo transactions and a lack of regulations to bind holders to disclose their positions.” Typically, only actual defaults on payments cause owners to reveal themselves!

In the face of such complexity, international agreements for debt restructuring become next to impossible. So the onus now really lies with the two countries in which most external debt contracts and bond issues occur: the US and the UK. Too often, their legal systems are used to prevent effective debt restructuring and allow rogue holdout creditors to call the shots. To deal with global debt issues, it is now necessary for the legal systems of these two countries to be made more flexible and accord international debtors the same rights and privileges that are routinely offered to individual and municipal debtors within their countries.

Such a change is not likely to come about without significant political pressure, but such pressure would be in both the global interest and the interests of citizens within these countries.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on June 14, 2021)